A project led by a UNC Charlotte doctoral candidate along with local high school students and experts is tracing the history of the Black educational experience in Charlotte and finding wisdom in the past to apply to the issues of today.

The brainchild of Jimmeka Anderson, a Ph.D. student in the Curriculum and Instruction - Urban Education program, “The Education of Blacks (1920 - 2020) Online Youth Exhibition” project shares the educational experience, past and present, of Charlotte’s Black population. The initiative captures the historically marginalized experience in the educational system through digital media.

The brainchild of Jimmeka Anderson, a Ph.D. student in the Curriculum and Instruction - Urban Education program, “The Education of Blacks (1920 - 2020) Online Youth Exhibition” project shares the educational experience, past and present, of Charlotte’s Black population. The initiative captures the historically marginalized experience in the educational system through digital media.

“I am a Charlotte native. I grew up in Charlotte-Mecklenburg schools, and as a Black child I never learned the history of Blacks in Charlotte, nor understood what was happening politically in my community to influence education until I became a Ph.D. student,” Anderson explained. “I believe if students and the Black community were more educated on how the schools and legislation has influenced the education of Black children, there would be a greater desire to invest in reform efforts that benefit marginalized students.”

The project, which was funded by the North Carolina Humanities Council, was developed through student-focused historical workshops led by noted scholar Pamela Grundy and archival research sessions led by the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library. Anderson wrote and coordinated the grant that earned the funding as part of her role as a doctoral student and graduate assistant with the Urban Education Collaborative.

Students from Victory Christian High School, Myers Park High School, Mallard Creek High School, Vance High School (to be renamed Julius Chambers High School) and Druid Hills Academy participated in the workshops, and students from the Carolina School of Broadcasting recorded and edited interviews with community members. Anderson’s nonprofit, I AM not the MEdia, contributed digital media workshops. After completing the workshops, students created an archival website with photographs, audio interviews and digital artifacts that capture the Black educational experience in Charlotte across four eras.

“It's crazy to me that I have lived in this city, and I am Black, and I've never heard a single thing about any of this that is being shared with us,” said student Gabrielle McDonald. “I have had much thought about what I've learned, I realized I don't believe we talk about the history of Charlotte enough. Another thing that was a surprise is how far we’ve come. On the other hand, I feel like Charlotte and our community could be better.”

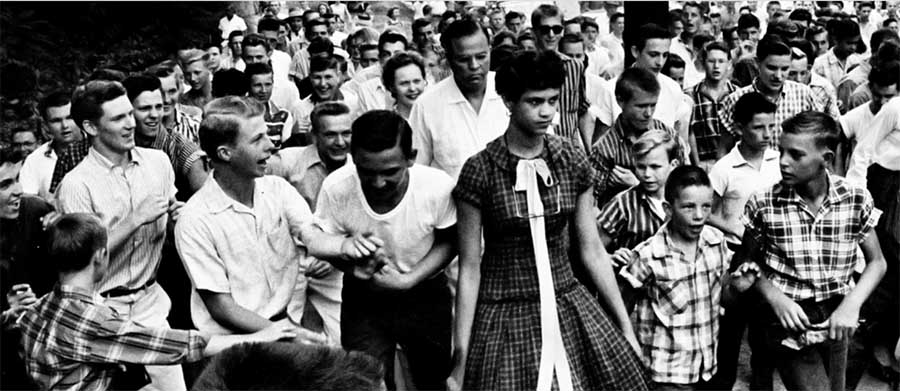

Charlotte is an appropriate venue. The city has been, and continues to be, a national focal point for dialogue on race and public schools. It’s a discussion that came to a head with landmark Supreme Court decisions affirming, then later overturning, the use of busing to create racial balance in schools.

“[It’s] a remarkable resource for exploring education history in one of the South’s major cities. This website gives you tools to delve deeper into a century of change,” said Tom Hanchett, a Charlotte community historian.

Today, the school district is North Carolina’s most segregated, according to a 2018 report from the North Carolina Justice Center. Recent declines in graduation rates have hit the hardest among high poverty neighborhood schools and impact predominately Black, Hispanic and economically disadvantaged students.

Anderson believes that creating conversations that connect the past to potential remedies for the future is critical toward building social capital and empowering economic mobility in Charlotte.

“The Education of Blacks in Charlotte” is a continuation of Anderson’s work on youth media literacy through I AM not the MEdia, which empowers teens and young adults to become conscious viewers of the media, critical decision makers and to embrace their individuality and uniqueness through media literacy and creation. Anderson said she hopes to help youth “analyze how marginalized populations are influenced by power structures and how media can be used to oppress or liberate.”

For student Ariah Cornelius, participating brought on a sense of optimism and appreciation.

“The thing that stuck with me the most is to prize and cherish the opportunities that are granted to me because those who made it possible did not have the same access but created the possibility for me to have access. I was inspired by all of the information that I learned from this research and deeply appreciative of those who blazed the trail for better opportunities for those of us who would follow them,” she said.

In the coming months, Anderson and her team will begin hosting community sessions with educators and parents on how the exhibit can be used as a resource to teach the history of Black education in Charlotte.