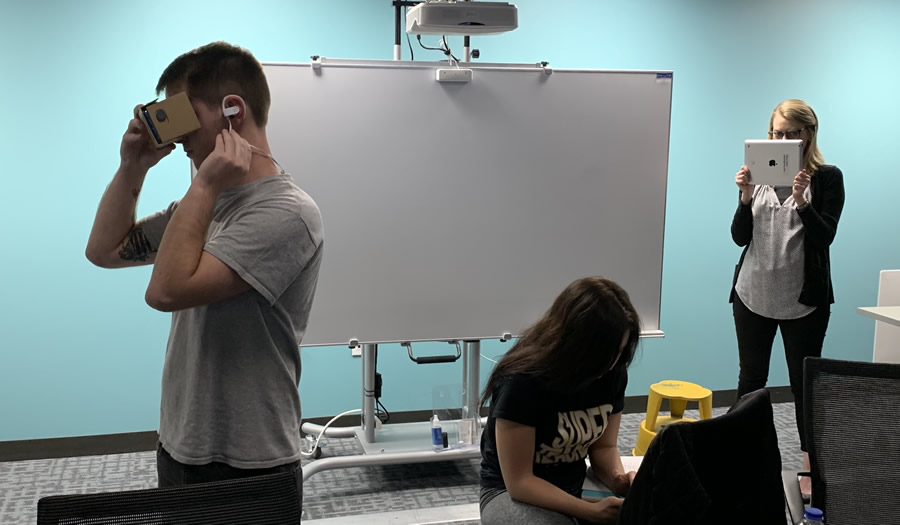

Education students at UNC Charlotte are now using virtual reality (VR) to prepare for real-life classrooms, in a program that looks to reshape the way future teacher candidates learn about how students and teachers interact. Meghan Barnes, an English education professor from the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences, and Hilary Dack from the Cato College of Education developed the program, which allows students to interact with videotaped K-12 classes through VR headsets.

“I first started thinking about VR when the Cato College of Education began developing more and more online and distance education courses for teacher candidates,” said Barnes. “I felt that VR videos could provide a more immersive experience for our teacher candidates as they analyze teachers’ moves in the classroom.”

During summer 2019, Barnes and Dack received a grant from UNC Charlotte to begin their work on the program. As part of the first phase of the program, in fall 2019, this program was piloted in one of Barnes’ classes with English language arts teacher candidates.

“I was honestly a little uncertain about seeing VR in a classroom because I wasn’t sure how a professor could effectively utilize it so that students could learn,” said student Emily Hoar. “I definitely think this method of learning was beneficial because it helped me envision what the environment and the discourse might be like in the classroom.”

The second phase will begin in spring 2020 in two of Dack’s courses.

“Because we’re analyzing how teachers in the videos use practices like eliciting student thinking and setting up small-group work, our focus will be on the ‘teaching moves’ shown in the lessons, rather than the language arts content,” said Dack, an assistant professor in the Department of Middle, Secondary and K-12 Education. “So the videos will provide useful opportunities to deconstruct a teacher’s practice regardless of candidates’ licensure areas.”

Barnes and Dack eventually hope to incorporate VR into online teacher prep courses that support distance education students.

“As the college continues to move toward a more practice-based approach to teacher education, we hope that analysis of VR videos in combination with contextual information can support our teacher candidates in gaining deeper understandings of teachers’ diverse practices in the classroom,” said Barnes.

According to Dack, the method of using videos in a classroom setting as a way of preparing teacher candidates is not new. However, videos alone can be limiting in how much they allow candidates to learn real-world applications and techniques, and they typically do not provide very much context.

“The videos and the VR technology respond directly to those problems of traditional videos used in teacher education,” said Dack. “With [the VR technology], candidates feel like they’re seeing real classrooms with real students and teachers, and they get to see classrooms that reflect the diversity of the students they’ll likely work with in their own careers,” said Dack. “At the same time, they’re able to view the whole classroom and can zoom in on any teacher or student action that seems relevant at a given moment in time. It’s a much more effective tool to support their deconstructing practice.”

At a time in which teacher preparation programs face numerous pressures, Barnes and Dack believe this unique method of teaching could be a key to opening up new opportunities for teacher candidates, as well as a way of building connections between the colleges across the University, classroom teachers and K-12 students.