A new College of Education study is revealing the effects of cross-cultural interactions in the classroom, and how educators can better communicate with students from different backgrounds.

Published in the journal Teaching Exceptional Children, the research “A Journey, Not a Destination: Developing Cultural Competence in Secondary Transition” looks specifically at educators who help culturally and linguistically diverse special education students transition from school to the adult world.

The definition of the term and the attributes that make an educator culturally competent have evolved over time. A widely accepted definition cited in the study describes it as “an ability to integrate and translate knowledge about groups of people into attitudes, standards, policies, and practices that increase the quality of services and produce better outcomes.”

Cultural competence is especially important for special educators, the article noted. Youth with disabilities face greater challenges than their typically developing peers, and “rates of high school graduation and employment outcomes different greatly between socioeconomics status, disability category, gender, and race and ethnicity.” This is compounded by the fact that the student population is diversifying at a rate faster than that of special educators, the majority of whom are white females from middle-class backgrounds.

Tiana Povenmire-Kirk is a project coordinator at the College of Education and one of the study’s co-authors. She said cultural competence training can make a major difference in the classroom.

“Although research indicates it is important that students see individuals who have similar backgrounds in positions of authority, cultural competence development can greatly improve the services all educators deliver, and the experiences of students from diverse backgrounds,” said Povenmire-Kirk.

Somewhat paradoxically, the first step toward developing cultural competence is not studying other cultures but looking closely at one’s own. It's in response to this introspection that real progress can occur, researchers concluded.

“Recognizing that each of us has a culture and that conflicts occur in the interaction between two cultures represents a crucial improvement over providing discrete bits of generalized information that may or may not apply to members of a given group,” Povenmire-Kirk stated. “For many members of the dominant culture, acknowledging that we have a culture is a critical first step to recognizing how much we bring to each interaction.”

In doing so, educators may begin to realize that “the assumptions and values that we bring to the table will inform the choices that we offer, the options we even consider possible for a given student,” Povenmire-Kirk continued.

Cultural values’ effects on the transition process are often subtle, but their scope is expansive, she noted. “Some skills often expected in the job search process such as direct eye contact with authority figures, shaking hands and speaking well of oneself can be impacted by culture in myriad ways. Other issues like living independently, leaving home, working for wages, going to college and even working after dark are affected by culture, community and family of each individual.”

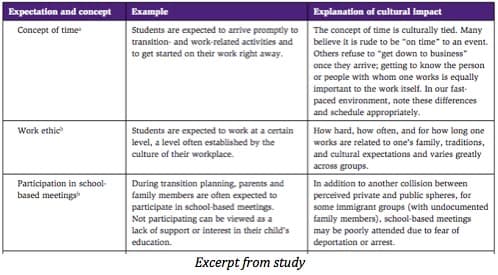

The study included tables outlining in detail how various transition-related activities can be affected by culture and offered strategies for developing cultural competence. It painted a picture of these tactics in action using hypothetical case studies.

In the end, Povenmire-Kirk said the theory isn’t necessarily about reconciling cultural differences but about being conscious that they exist and have an influence on how people interact.

“We are not suggesting that anyone change their beliefs, values or expectations, only that they be aware that they have them and that others may or may not share them,” said Povenmire-Kirk, who added that the effects of a culturally competent educator reach beyond the schoolhouse door, teaching students to understand and respect one another.

“Just as children are more polite when their caregivers model use of good manners, using ‘please’ and ‘thank you,’ so, too, do students learn respect for difference when it is modeled for them, and when they are treated with respect.”